Global Muslim Population Exceeds 2 Billion

Research expects Islam to end Christianity’s long reign as the world’s largest religion.

Rabat – The world’s Muslim community is estimated to have reached a total of 2,006,931,770 this week, the Global Muslim Population website reported earlier this week.

Muslims thus represent more than 25% of the global population of over 8 billion people, added the report, noting that Islam is the second largest religion in the world after Christianity.

Islam is the official religion in 26 countries across Asia and Africa, said the report, adding that it is also the fastest-growing religion in the world.

A 2017 report by the Pew Research Center indicated that Muslims are “the world’s fastest-growing religious group,” projecting Islam to overtake Christianity as the world’s largest religion.

“Muslims will grow more than twice as fast as the overall world population between 2015 and 2060 and, in the second half of this century, will likely surpass Christians as the world’s largest religious group,” indicated the report.

It added that babies born to Muslim parents will start to outnumber those born to Christians by the year 2035.

Read also: On Being A Moroccan Muslim Woman

The world’s population is expected to grow by 32% in the next decades. However, the Muslim population is projected to increase by 70%, from 1.8 billion in 2015 to nearly 3 billion in 2060.

In addition, the report expects religious switching to “hinder” the growth of Christianity by an estimated 72 million people between 2015 and 2060. However, it suggested that religious switching will not have a “negative net impact” on Muslim population growth.

FULL ARTICLE FROM MOROCCO WORLD NEWS

******

Key Findings From the Global Religious Futures Project

he Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures project seeks to understand religious change and its impact on societies around the world. Since 2006, it has included three main lines of research:

- Surveys in more than 95 countries (and 130 languages) asking nearly 200,000 people about their religious identities, beliefs and practices

- Demographic studies that use censuses and other data sources to estimate the size of religious groups, project how fast they are growing or shrinking, and analyze mechanisms of religious change

- Annual tracking of restrictions on religion in 198 countries and territories

Pew Research Center – a nonprofit, nonpartisan fact tank – conducts these studies and makes them freely available to the public. The Center does not promote any religious or spiritual beliefs (or nonbelief).

The Global Religious Futures (GRF) project is jointly funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts and The John Templeton Foundation. Here are some big-picture findings from the GRF, together with context from other Pew Research Center studies.

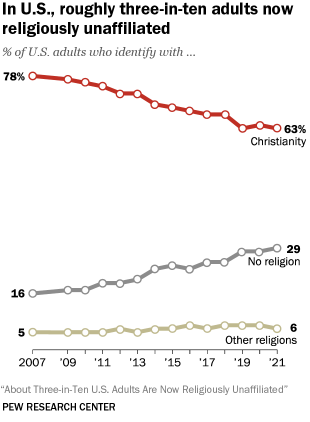

People are becoming less religious in the U.S. and many other countries

The U.S. public seems to be growing less religious, at least by conventional measures. The percentage of American adults who identify as Christian has been declining each year, while the share who do not identify with any religion has been rising rapidly. (Members of non-Christian religions, such as Judaism, Islam, Hinduism and Buddhism, to name just a few, make up a smaller share of Americans.)

This pattern began a few decades ago, and it is projected to continue into the foreseeable future. Moreover, affiliation – whether people say they belong to a religion – is not the only indicator that is dropping. Religious observance also has fallen in surveys asking U.S. adults how often they attend religious services, how frequently they pray, and how important they consider religion to be in their lives.

The United States is far from alone in this way. Western Europeans are generally less religious than Americans, having started along a similar path a few decades earlier. And the same secularizing trends are found in other economically advanced countries, as indicated by recent census data from Australia and New Zealand.

Population growth is faster in highly religious countries

At the same time, large parts of the world now have low birth rates. This includes not only Western Europe and North America, but also China, where a majority of the world’s religiously unaffiliated population lives (and where the government imposed a “one-child policy” from 1980 until 2016).

FULL ARTICLE FROM PEW RESEARCH

*****

Want to know more about Muslims and Islam? We’ve got an email course for you

With an estimated population of 1.8 billion, Muslims are the world’s second-largest religious group, after Christians. But our surveys have found that about half of Americans – as well as most Western Europeans – say they know little or nothing about Islam.

Try our email course on Muslims and Islam

Learn about Muslims and Islam through four short lessons delivered to your inbox every other day. Sign up now!

Pew Research Center has conducted more than a decade’s worth of global research on religion, including surveys of Muslims in 39 countries, three comprehensive surveys of Muslim Americans, several demographic studies of the world’s major religions (including population growth projections), and a series of surveys that measure how people living in the U.S. and Europe view Muslims and Islam.

We have drawn on this research to answer questions such as: How differently do Muslims around the globe practice their faith? What do they believe? How are they viewed in public opinion in various Western countries? How much discrimination do they face?

We now have distilled some key findings from this data into four email mini-lessons, to help interested people develop a better understanding of Muslims and Islam. Sign up, and you’ll receive an email every other day for about a week. If you want to dig deeper, the emails will offer links to work by the Center that supply more detailed information. As with all our research, it’s free. At the end, there will be a quiz to help you see what you’ve learned.

Sign up to take the course here. We hope you get a lot out of it. And please tell us what you think.

——————————————–

*****

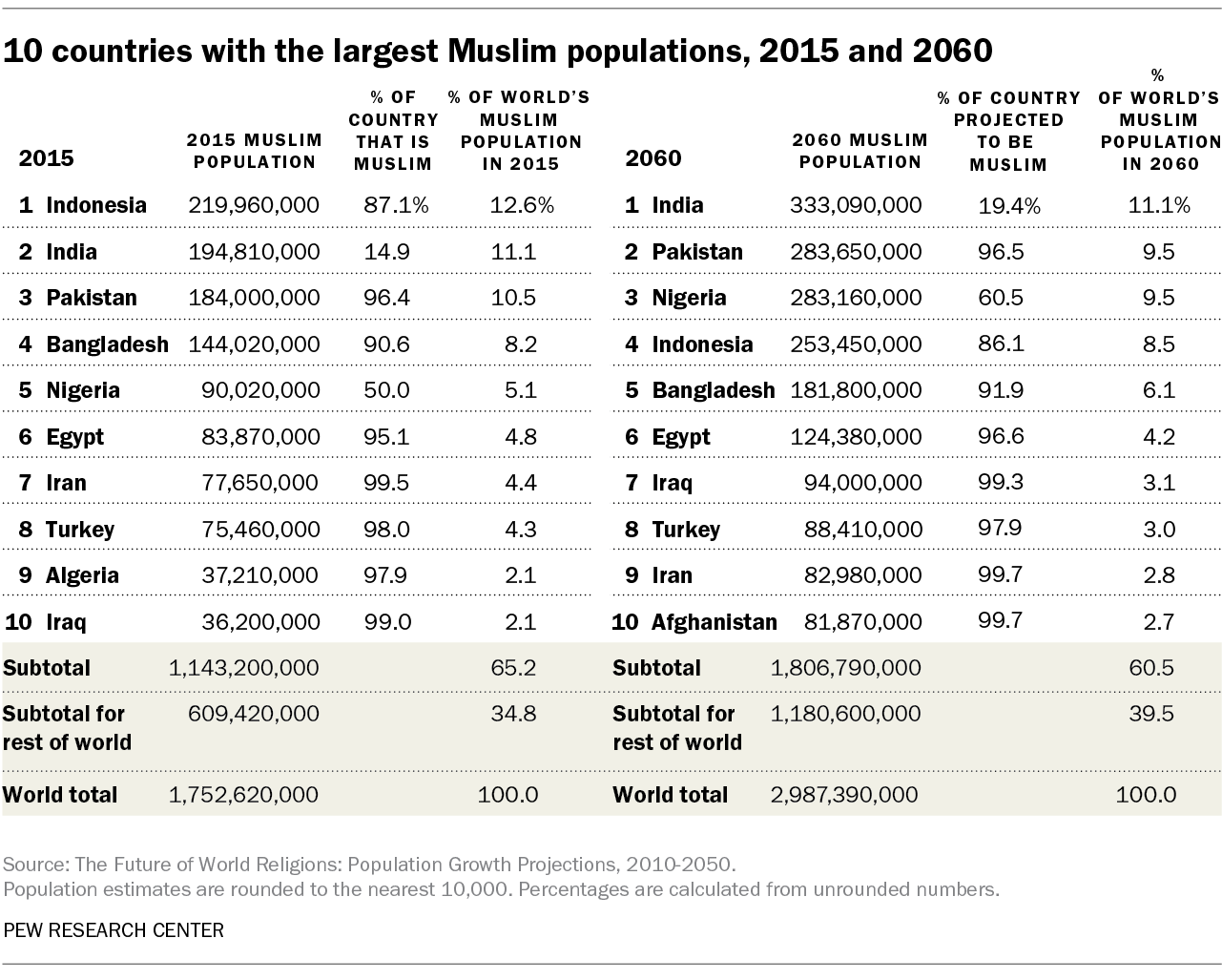

The countries with the 10 largest Christian populations and the 10 largest Muslim populations

Muslims take part in the Eid al-Fitr prays at the Syrian Mosque, at the Ikoyi district, in Lagos, on June 25, 2017. Eid al-Fitr festival marks the end of the holy Muslim fasting month of Ramadan during which devotees are required to abstain from food, drink and sex from dawn to dusk. / AFP PHOTO / PIUS UTOMI EKPEI (Photo credit should read PIUS UTOMI EKPEI/AFP/Getty Images)

“Top 10” lists can often be helpful in displaying and illuminating data. For example, the two tables of countries with the largest Christian and Muslim populations featured here reveal differences in the concentration, diversity and projected changes in the world’s two largest religions.

The two lists show that the global Muslim population is more heavily concentrated in Islam’s main population centers than the global Christian population is for Christianity, which is more widely dispersed around the world. Indeed, about two-thirds (65%) of the world’s Muslims live in the countries with the 10 largest Muslim populations, while only 48% of the world’s Christians live in the countries with the 10 largest Christian populations.

To put it another way, more than half (52%) of the world’s Christians live in countries other than those with the 10 largest Christian populations, while this is true for just over a third (35%) of the world’s Muslims. In absolute terms, there are twice as many Christians (1.2 billion) as there are Muslims (609 million) living in countries that are not on their religion’s top 10 list.

FULL ARTICLE FROM PEW RESEARCH

——————————–

Black Muslims account for a fifth of all U.S. Muslims, and about half are converts to Islam

Muslim worshippers gather at the US Bank Stadium for prayer and festivites for Eid al-Adha on August 21, 2018 in Minneapolis, Minnesota. – The US Bank Stadium, home of the National Football League’s Minnesota Vikings, is hosting thousands for the event that organizers are calling Super Eid. The holiday, one of the holiest of the year for Muslims, honors the Prophet Ibrahim, also known as Abraham in Judaism and Christianity, and comes at the end of annual hajj pilgrimage. (Photo by Kerem Yucel / AFP) (Photo credit should read KEREM YUCEL/AFP/Getty Images)

This is one of an occasional series of posts on black Americans and religion.

Even in the early 20th century, when Islam had little presence in most parts of the United States, the religion had a foothold in many black urban communities. Today, black people (not including those of Hispanic descent or mixed race) make up 20% of the country’s overall Muslim population, according to a 2017 Pew Research Center survey.

Still, Muslims make up only a small portion of the overall black population in the United States. The vast majority of black Americans are either Christian (79%) or religiously unaffiliated (18%), while about 2% of black Americans are Muslim.

About half of black Muslims (49%) are converts to Islam, a relatively high level of  conversion. By contrast, only 15% of nonblack Muslims are converts to Islam, and just 6% of black Christians are converts to Christianity.

conversion. By contrast, only 15% of nonblack Muslims are converts to Islam, and just 6% of black Christians are converts to Christianity.

Black Muslims are like black Americans overall in that they have high levels of religious commitment. For instance, large majorities of both black Muslims and black Christians say religion is very important to them (75% and 84% respectively). This is a higher level of commitment than for nonblack Muslims (62%). Black Muslims are also more likely than other Muslims in the U.S. to perform the five daily prayers (55% vs. 39%).

FULL ARTICLE FROM PEW RESEARCH.ORG

*****

Muslims and Islam: Key findings in the U.S. and around the world

Muslims are the fastest-growing religious group in the world. The growth and regional migration of Muslims, combined with the ongoing impact of the Islamic State (also known as ISIS or ISIL) and other extremist groups that commit acts of violence in the name of Islam, have brought Muslims and the Islamic faith to the forefront of the political debate in many countries. Yet many facts about Muslims are not well known in some of these places, and most Americans – who live in a country with a relatively small Muslim population – have said they know little or nothing about Islam.

Here are answers to some key questions about Muslims, compiled from several Pew Research Center reports published in recent years:

How many Muslims are there? Where do they live?

There were 1.8 billion Muslims in the world as of 2015 – roughly 24% of the global population – according to a Pew Research Center estimate. But while Islam is currently the world’s second-largest religion (after Christianity), it is the fastest-growing major religion. Indeed, if current demographic trends continue, the number of Muslims is expected to exceed the number of Christians by the end of this century.

There were 1.8 billion Muslims in the world as of 2015 – roughly 24% of the global population – according to a Pew Research Center estimate. But while Islam is currently the world’s second-largest religion (after Christianity), it is the fastest-growing major religion. Indeed, if current demographic trends continue, the number of Muslims is expected to exceed the number of Christians by the end of this century.

Although many countries in the Middle East-North Africa region, where the religion originated in the seventh century, are heavily Muslim, the region is home to only about 20% of the world’s Muslims. A majority of the Muslims globally (62%) live in the Asia-Pacific region, including large populations in Indonesia, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Iran and Turkey.

FULL ARTICLE FROM PEW RESEARCH

———————————————-

Reports of Islamophobia: 1997 and 2017

THE ROAD TRAVELLED

Earlier this month the Runnymede Trust launched a new report, Islamophobia: Still a challenge for us all, to mark the 20th anniversary of the publication of the landmark 1997 report, Islamophobia; A challenge for us all. The significance of the original Report is hard to over-estimate. While it is the case that it did not coin the term Islamophobia, it certainly gave it legs. And while it is also true that the report did not end Islamophobia, it did indict it.

The 1997 report was the first comprehensive combined survey and policy intervention on an increasingly prominent phenomenon and against the context of heightened global problematisation of Muslims as Muslims. This is worth remembering for two reasons. Firstly, whatever its final form as a document, the consultative nature of the work which fed into its pages generated a momentum and a sense of stake-holding important to its reception and impact. Whether adopted as leverage or contested in whole or in part, the report and the momentum of its discussion produced Muslim agency over Muslim agendas. The publication of the report propelled Islamophobia into public consciousness. It shaped the national and global conversation, even if much of that conversation was only to contest the vocabulary that the report sought to establish. Second, because it is worth being reminded that already in 1997 the report was a response to diverse interrelated historical shifts, both local and transnational: the post third worldist and post-67 global resurgence of Muslims signified by the Revolt of Islam; the increasing debasement of the grand narratives of modernisation come-secularisation in the social sciences; cumulative postcolonial and post-cold war challenges to the Eurocentric world order; the identification and ascriptive reclassification of ethnically marked and immigrant populations as Muslim, and concomitant mobilisations over the way in which existing race-relations based anti-discrimination legislation afforded them only uneven and inadequate protection, recourse, and redress as Muslims. This isn’t just about recasting a twenty year view into a longer genealogy. Against presentist fixation on framing the Muslim Question in the horizon of 9/11, it bears remembering that the report was published four years before George W. Bush declared the ‘war on terror’, and that in some ways this never-ending war was as much a reflection of Islamophobia as it was its intensification.

The 2017 report does not repeat the impact of the original report; perhaps never could. In any case, it is a very different document. The 1997 report was the work of a commission; the present report is an edited collection. It is based neither on community consultation, nor on new research and evidence into the policy areas it covers, but rather on commissioned chapters by academics summarising their research in different registers. Each chapter, as their bibliographical references mostly attest, speaks in an individual voice, and the volume makes little effort to engage let alone convey or build upon the mounting and increasingly diverse body of academic scholarship on Islamophobia produced across the world, including in two specialist journals, and numerous reports. Even its most significant departure from the 1997 report, that of defining Islamophobia as anti-Muslim racism, is eroded by this lack of engagement. There is something to be said for an edited collection of single-theme focused chapters, but the absence of connection and engagement across the chapters is problematic.

The difference between the two reports provides a useful index of how Islamophobia as concept and phenomena has changed in the intervening twenty years. What follows is a brief comparative and relational analysis of the two reports as a way of arguing for the need for a theory of Islamophobia which can broaden the diet of examples by which we can apprehend this phenomenon. Theorizing Islamophobia is important not just because of reasons of intellectual aesthetics but because only such an account can turn the noise of data into facts, organise our perceptions and fortify any recommendations which we care to make.

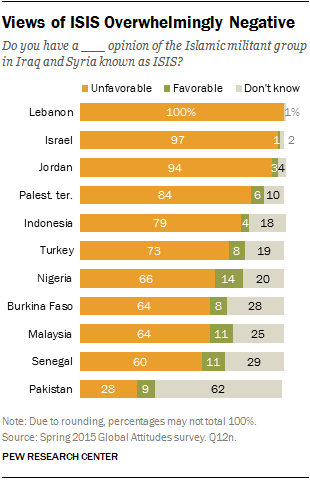

In nations with significant Muslim populations, much disdain for ISIS

Recent attacks in Paris, Beirut and Baghdad linked to the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) have once again brought terrorism and Islamic extremism to the forefront of international relations. According to newly released data that the Pew Research Center collected in 11 countries with significant Muslim populations, people from Nigeria to Jordan to Indonesia overwhelmingly expressed negative views of ISIS.

One exception was Pakistan, where a majority offered no definite opinion of ISIS. The nationally representative surveys were conducted as part of the Pew Research Center’s annual global poll in April and May this year.

nationally representative surveys were conducted as part of the Pew Research Center’s annual global poll in April and May this year.

In no country surveyed did more than 15% of the population show favorable attitudes toward Islamic State. And in those countries with mixed religious and ethnic populations, negative views of ISIS cut across these lines.

In Lebanon, a victim of one of the most recent attacks, almost every person surveyed who gave an opinion had an unfavorable view of ISIS, including 99% with a very unfavorable opinion. Distaste toward ISIS was shared by Lebanese Sunni Muslims (98% unfavorable) and 100% of Shia Muslims and Lebanese Christians.

FULL ARTICLE FROM PEW RESEARCH

************